Key words: technology, new technologies, computers, writing, Walter Ong, Plato

What we understand by technology is not always clear. Realising that most of the things that surround us are technology should help us consider new technologies from a more open and critical perspective.

___________

From an anthropological point of view, the word technology could be defined as “the body of knowledge available to a civilization that is of use in fashioning implements, practicing manual arts and skills, and extracting or collecting materials” (The American Heritage Dictionary).

Whenever we hear the word technology, however, we tend to instantly associate it with computers, electronic appliances, cell phones and the like. If we understand technology in its broader sense, we should also think of writing, books or pens as technologies. The difference between a pen and a cell phone is that cell phones are later technologies, but no doubt they’re both technologies in the end.

Whenever we hear the word technology, however, we tend to instantly associate it with computers, electronic appliances, cell phones and the like. If we understand technology in its broader sense, we should also think of writing, books or pens as technologies. The difference between a pen and a cell phone is that cell phones are later technologies, but no doubt they’re both technologies in the end.

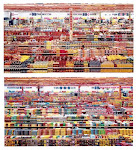

The problem seems to be that we tend to naturalise those technologies that have been with us for a long time and look at them acritically. Nobody, for example, sees anything wrong in a book; but new technologies like computers are commonly looked at with distrust and apprehension. Many people see books as natural elements, while they consider computers openly artificial things. Or, what is even less clear, they think books are less artificial than computers, as if there was anything natural in a book. They would attack computers by dubbing them cold and impersonal, but nobody would say the same of books, even though the way of approaching text is essentially the same, and books –unlike computers- are not suited for real-time communication.

Negative reactions towards new technologies have always been present throughout history, although in different extents. The Luddites in 19th century

Negative reactions towards new technologies have always been present throughout history, although in different extents. The Luddites in 19th century

Walter Ong, in a book subtitled "The Technologizing of the Word," writes that “most persons are surprised, and many distressed, to learn that essentially the same objections commonly urged today against computers were urged by Plato in the Phaedrus and in the Seventh Letter against writing” [2]. The author explains:

Writing, Plato has Socrates say in the Phaedrus, is inhuman, pretending to establish outside the mind what in reality can be only in the mind. It is a thing, a manufactured product. The same of course is said of computers. Secondly, Plato’s Socrates urges, writing destroys memory. Those who use writing will become forgetful, relying on an external resource for what they lack in internal resources. Writing weakens the mind. Today, parents and others fear that pocket calculators provide an external resource for what ought to be the internal resource of memorized multiplication tables (…)

Ong also quotes Hieronimo Squarciafico, who in 1477 expressed similar misgivings towards print. But, just as Squarciafico still promoted the printing of books, Plat o also wrote. This paradox can prove even greater if we agree with Ong, who -citing

o also wrote. This paradox can prove even greater if we agree with Ong, who -citing

Of course, together with the pessimistic views on new technologies, we also have the optimistic ones. Some people during the 18th century and later thought power engines would make labourers’ life easier, turning the world a better place. Before that, some thought print would make everyone wiser. Similar ideas were also heard about television during the aftermath of the Second World War, and can still be heard about computers.

The pessimistic and optimistic views on technology usually fall under the terms technophobia and technophilia –dislike or love for new technologies. Placing ourselves on any of these extremes implies avoiding the task of consciously pondering and analysing technologies. I have for me that if we really want to arrive at a sensible perception of a particular technology, we should get to know it, use it, apply it, see its benefits and disadvantages, and be critical about it. No technology is hundred per cent good or bad [3]. Sometimes it is us who either feel unconsciously charmed by new fashionable things, or who can’t be flexible enough to challenge our habits and try something that is not what we’re used to.

__________

[1] Fisch’s What if… presentation gives a clear survey of this reluctance to new technologies in education. I’ve already included this video in a previous post.

[2] Ong, Walter (2002) Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word.

[3] Langdon Winner (1983) analyses whether certain values and power relations are inherent to some technologies. In his article Do Artifacts have Politics? the author answers positively to the question in the title.

.gif)