Far from being objective reproductions of the world, photographs imply taking creative and ideological decisions that may bias or alter reality. Using photographs as sources, then, should require from us a skeptical and critical attitude.

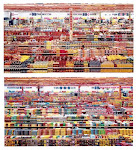

The problem of representation has already engaged us in several class discussions. Some months ago we expanded one of these debates here (that time, concerning maps). A few meetings ago in L&C III, a new debate on representation took place, this time regarding photographs. One of the students was dealing with the topic of cannibalism in the novel Robinson Crusoe and reading on the controversy about the factual existence of anthropophagy, whether past or present. When looking for some images for his class presentation in Google, he came across the following photograph under the heading “cannibalism.”

After looking at this apparently self-evident portrait of reality, we posed this skeptic question –Can photographs lie?

The same we had done before with portraits and maps, but we must admit that even when we can easily accept the fabrication that underlies painting or cartography, we definitely tend to see objective reality in a photograph [1]. People seldom reflect or perceive that photographs are representations and fabrications as well, and that, although constrained in some way by objective reality, this constraint is to not avail enough to render photographs airtight reproductions of that reality. There are a few photographic and semiological concepts that can give us a hand in this respect.

The first one is the concept of frame. Reality is a continuum. There are no physical limits to reality. If we open our eyes and turn our heads around, we will perceive that reality is not fragmented. No camera can reproduce this perception (not even a cinematographic one). Cameras can only take discrete fragments of reality. They can only select small bits of it, and, in doing so, most of reality is left aside. When framing, the photographer is leaving aside everything that is beyond the four boundaries of the frame, plus everything that is behind the camera, and even everything that is hidden by other objects within the limits of the frame. Thus, any photography contains an extremely simplified view of reality. Can we trust photographs then? In the example above mentioned, for instance, some doubts could arise –Where was this photograph taken from? What is the situation around the main character? Can we really explain this photograph without its context?

The first one is the concept of frame. Reality is a continuum. There are no physical limits to reality. If we open our eyes and turn our heads around, we will perceive that reality is not fragmented. No camera can reproduce this perception (not even a cinematographic one). Cameras can only take discrete fragments of reality. They can only select small bits of it, and, in doing so, most of reality is left aside. When framing, the photographer is leaving aside everything that is beyond the four boundaries of the frame, plus everything that is behind the camera, and even everything that is hidden by other objects within the limits of the frame. Thus, any photography contains an extremely simplified view of reality. Can we trust photographs then? In the example above mentioned, for instance, some doubts could arise –Where was this photograph taken from? What is the situation around the main character? Can we really explain this photograph without its context?

The act of framing goes hand by hand with another concept, that of point of view. This concept emphasizes the presence of a subject, the photographer, with a particular understanding of the world and moved by particular interests. If the camera, as we said before, can only take  discrete portions of a continuous reality, then it is the photographer who will decide what of this continuum to portray. And this choice will be determined by the photographer’s position, but also by his ideology, what he considers relevant to be photographed. Two people holding cameras in front of a singular event will not take the same pictures. What we see when we see a photograph is the result of a personal choice, somebody’s choice. We would ask then, going back to our previous example –Who took the photograph? Why? What was he trying to show? Can his choice condition, in any respect, our interpretation of the event?

discrete portions of a continuous reality, then it is the photographer who will decide what of this continuum to portray. And this choice will be determined by the photographer’s position, but also by his ideology, what he considers relevant to be photographed. Two people holding cameras in front of a singular event will not take the same pictures. What we see when we see a photograph is the result of a personal choice, somebody’s choice. We would ask then, going back to our previous example –Who took the photograph? Why? What was he trying to show? Can his choice condition, in any respect, our interpretation of the event?

Attempting to answer all these questions may help us see that photographs alone carry not much more than uncertainty [2]. Susan Sontag explains that “photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy,” and she adds that “in fact, we never understand anything through photographs.” [3]

However, most people would still feel that they do get meaning from most of the photographs they daily come across with. In most of the cases, this is due to the fact that photographs rarely come along on their own, but they are usually immersed in a textual environment from  which they also derive meaning. This leads to a third concept of interest, the concept of surround (context). Words, although not a part of the photographic art itself, are very much connected to the use of photographs, mostly in the press. Captions are the most typical ‘textual anchors’ for photographs, although headings, subheadings and articles can also function as such. Captions are explanatory words usually attached to photographs. These words are of utmost importance for the simple fact that they can completely bias the interpretation of an image, and, in doing so, serve us as proof of the limited capacity of evidence that photographs possess [4]. Cartoonist Quino reflects on this interaction between text and image through a cartoon in which completely different captions are attached to the same photograph, entirely affecting and transforming its meaning (click on image for full cartoon). But newspapers give us daily example of this relationship, providing we critically face the task of ‘reading’ images. As to our original example, we can still wonder whether we would still see an act of cannibalism had any other label been attached to it. What if the caption had read “Angian warrior celebrating their victory at Jartar”?

which they also derive meaning. This leads to a third concept of interest, the concept of surround (context). Words, although not a part of the photographic art itself, are very much connected to the use of photographs, mostly in the press. Captions are the most typical ‘textual anchors’ for photographs, although headings, subheadings and articles can also function as such. Captions are explanatory words usually attached to photographs. These words are of utmost importance for the simple fact that they can completely bias the interpretation of an image, and, in doing so, serve us as proof of the limited capacity of evidence that photographs possess [4]. Cartoonist Quino reflects on this interaction between text and image through a cartoon in which completely different captions are attached to the same photograph, entirely affecting and transforming its meaning (click on image for full cartoon). But newspapers give us daily example of this relationship, providing we critically face the task of ‘reading’ images. As to our original example, we can still wonder whether we would still see an act of cannibalism had any other label been attached to it. What if the caption had read “Angian warrior celebrating their victory at Jartar”?

__________

[1] This may be perhaps related to the everyday use we give to photographs. When we take photographs, we tend to look at them as objective reproductions of the moments we portray. We remain unaware of the many ‘artistic’ and even ‘ideological’ decisions we make before pressing the shutter.

[2] Even when they are not the only ones, these two first concepts –frame and point of view-, should serve to account for the artistic potential of photography.

[3] Susan Sontag, On Photography, quoted in Rocca and López (1995) Fotografía.

[4] Roland Barthes expands on most of these ideas in a classic study of press photography: “The photographic message.” Image Music Text, 1977.

.gif)